Through the Cross, Joy

Let us commend ourselves…

The first few days after the miscarriage were foggy and confusing. We were devastated. Afraid. Empty. We weren’t so much angry with God as numb. We shut down and withdrew. Why did we have to let go of the child we never met? Our emotional turmoil mirrored the winter weather: swirling snow shut everything down, and we were shut inside with our grief.

On the third day, God gave us a great gift to begin the slow process of healing. The blizzard dissipated, leaving everything hushed by a serene blanket of white snow. With everyone else inside to enjoy the day off, cozy with family before their fireplaces, the world outside remained quiet and pure, unspoiled. A new beginning. We alone emerged, tentatively, into that peaceful silence; tentatively, we entrusted part of our broken selves back to the Creator.

The next place we felt comfortable was in church, the Saturday night Vigil. We didn’t have to make meaningless small talk or look anyone in the eye. Others prayed by candlelight; we simply stood, holding onto the stillness from the previous day, letting the prayers wash over us. Out of the depths have I cried unto Thee. The prayers in preparation for Sunday, the day of resurrection already, but not yet. For Thy Name’s sake have I waited for Thee. We sat in the hushed service together, keeping watch before the icon of St. Anna the Prophetess, who is practiced at receiving children. We decided to commend our lost child to her, and to remember her with the same name. From the morning watch until night, let Israel hope in the Lord. Perhaps we could relearn how to commend ourselves to Christ, too.

Let us commend each other…

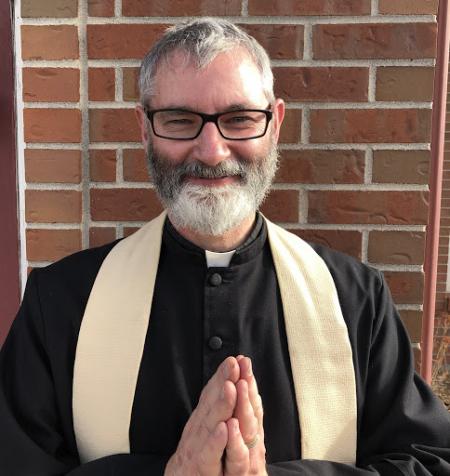

The close community at St. Vladimir’s carried us. Two priests came to see us shortly after it happened. They listened, they prayed; they assured us we could always call on them. They were kind and wise in their brevity. Perhaps one of the best lessons in the art of pastoral care.

The best gift our friends gave us at first was space. The second best was food. The evening after our loss came a knock at the door: no one there, just a bag of groceries and warm comfort food. And a note: We’ve been there; we’re here for you. Two of our closest friends. First there was a wave of guilt—how had we not known and acknowledged their pain? Then a stronger feeling, like a firm embrace: they loved us anyway, and there was nothing we could do about it.

We were not prepared for the gentle compassion we received. No one smothered us, but somehow, discretely, we were assured of everyone’s support. Family sent cards. A baby blanket in memoriam. We were even less prepared for the number of friends who had also miscarried. Obadiah. Innocent. Anna. They all had names, icons in the family prayer corner. How had we never noticed? Another couple of our closest friends invited us in. They had been there, too. You’ll never forget her. It still hits us unexpectedly after three years. Tears. Hugs. A deep bond that only comes with vulnerability and shared experience. Only in reflecting back do we see how we made it through.

With every act of kindness toward us, every tear shed with us, every prayer said secretly for us: our friends and family commended us to Christ when we were too lost and lethargic to know where to turn.

Let us commend all our life unto Christ our God.

Slowly the pain dulled, the sobs came less frequently, and we returned to life as usual. We mercifully receded from the spotlight. Nothing would ever be the same, but neither did it have to remain bleak. There were new pains, new fears, new questions; but we were finding a new resilience, and new wisdom. God had not left us during the most painful time of our lives, and in fact, we had never been closer to or more loved by our friends. As we practiced haltingly giving every thorny part of our life over to God, we found that the pain was not to be avoided or merely endured, but could actually be cultivated into the most precious fruitbearing tree. Now the flaming sword no longer guards the gates of Eden; Behold, through the Cross joy has come into all the world. Enter again into paradise.

After forty days of mourning, of lamentation, of the cold beginning of a New York spring—Pascha. In spite of ourselves, we dove into the celebration. Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life. Still not yet, not fully. But it felt closer; more certain. We grew to believe with more zeal than ever before. The child that never saw the light of day—her story did not, in fact, end before it began. We hope to meet her one day.

After forty days of paschal joy, of the hope of resurrection and reunion, of sunny days and blooming flowers, we had a memorial service and found out we were pregnant again. At the beginning of this year, our son was born, healthy and happy, by the grace of God. He cannot replace Anna, or erase the scar from our hearts; neither will he be overshadowed by her. Rather, he will grow up under the watchful protection of the Prophetess Anna and the Wonderworker Nicholas. And standing together in our prayer corner, before their icons and by their prayers, we three together will learn to commend ourselves, and each other, and all our life unto Christ our God.

-

Andrew, Melissa, and Nicholas Cannon live at St. Vladimir’s, where Andrew is in his final semester of his studies in the Master of Arts program.